When Ken Ward Jr. and I got to teach an investigative reporting class at West Virginia University in the fall of 2019, one of the regular assignments we had was to give students some state government report to read and ask them to generate newsworthy questions from it.

This exercise started out pretty rough. Even though questions are the backbone of journalism, there aren’t many journalism classes that assign them specifically. Usually the assignment is to write a story based on an event or interviews, and the assumption is that in doing that students will come up with relevant and interesting questions. But if you’re not covering a beat or an expert on a topic, investigative story ideas don’t just appear from thin air. They almost always derive from good questions.

At first, the questions we got were ok; often they were definitional, which makes sense since we were introducing new subjects and findings nearly every week. “What does X mean?” or “Why is Y important?” These aren’t bad questions, but they also indicate an introductory level of understanding of the subject. For a lot of journalism assignments, including investigative work, that’s a necessary step. The problem was that many of them focused on things that weren’t the most important thing.

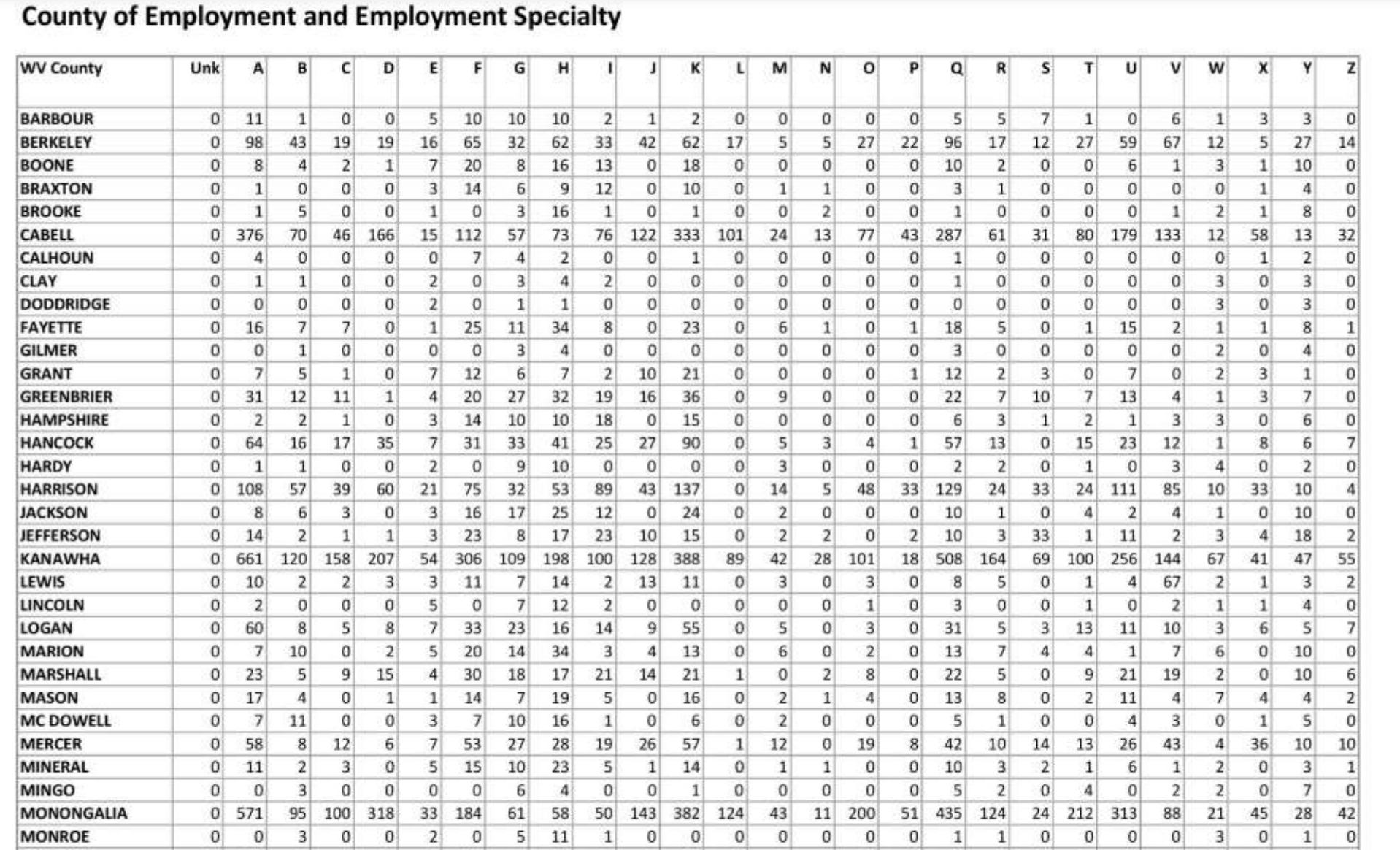

Here’s an example: one of the reports we had students read was from the West Virginia Board of Registered Nurses (see a more recent example here) showing, among other things, the number of registered nurses by county and specialty. The table looks like this:

The specialties are listed across the top, each letter corresponding to a value like “Cardiology” or “Pediatrics”. The letter “J” stands for “Maternal-Obstetrics”. Most of the questions we got were ones such as “Why do Cabell, Kanawha and Monongalia have so many more nurses?” which has a quick answer - they have more people living there. Look at the data longer, though, and you start to ask other, better questions, like: “How many WV counties have literally zero maternal/OBGYN nurses living there?” More than half the state’s counties have none, although there are maternal nurses living in other states who work in West Virginia. Or “What’s it like to be the only maternal health nurse in the whole county?” These are better questions that could lead to great stories.

The specialties are listed across the top, each letter corresponding to a value like “Cardiology” or “Pediatrics”. The letter “J” stands for “Maternal-Obstetrics”. Most of the questions we got were ones such as “Why do Cabell, Kanawha and Monongalia have so many more nurses?” which has a quick answer - they have more people living there. Look at the data longer, though, and you start to ask other, better questions, like: “How many WV counties have literally zero maternal/OBGYN nurses living there?” More than half the state’s counties have none, although there are maternal nurses living in other states who work in West Virginia. Or “What’s it like to be the only maternal health nurse in the whole county?” These are better questions that could lead to great stories.

In order to make this exercise more relevant to our WVU students, we looked at campus police incident reports. The information is not exactly in a useful format; it requires that people visit the site repeatedly and also “scrolls off” earlier reports after 90 days or so. In other words, a perfect candidate for scraping. So that’s what I did, writing some Python code to grab the latest reports and then using GitHub Actions to automate that process every day. The result is a CSV file with more than 13,000 rows.

Not many of us want to look at huge CSV files a lot, which is why we have other software to help us do that. The best software for this purpose is one that allows, even encourages, users to ask questions of the data. That’s what Datasette is great at. So after updating the CSV file with the latest WVU crime incident reports, I have GitHub Actions build out a Datasette instance to display it.

That brings me back to the title of this post: What is happening in Morgantown? Seems like a pretty basic question, but where it comes from is asking other questions of this data, and specifically grouping by and counting the number of reports. I start by grouping the reports by year (I’ve been collecting this data since the fall of 2019, so that year doesn’t have full data). Looking at those yearly totals, you can see 2020 stand out, which, given COVID, seems logical.

I’ve been looking at this data since 2019, and when you do that you start to get an idea of what the ebb and flow of it should look like. So when you see rare events, your brain might notice them. But that’s not the only way to find out if something has changed. Throughout the pandemic we heard a lot about students’ mental health struggles. Does that show up at all in campus police incidents? At the most extreme end we could look at references to suicide. It turns out that there are several incident titles that contain the word “suicide”, so let’s look at those.

One of Datasette’s key features is to allow you to execute arbitrary SQL statements, such as performing wildcard searches. Here are the results of searching for where title contains “SUICIDE”, grouped by year. There were nearly twice as many reports of attempted or threatened suicide recorded by WVU police in 2022 than in 2021. Nearly twice as many.

Which leads to these questions: what is happening in Morgantown? Is there an actual increase in suicidal behavior? Is this better reporting by police? An increased awareness of suicide leading to more willingness to report it? Something else entirely? I hope that someone in Morgantown is asking them.

A less extreme but very common incident on and around college campuses is a violation of alcohol laws. In West Virginia, these are known as “ABCC Violations”. Focusing on those, once again grouping by year, we can see that there were more violations reported in 2021 than in 2022. Interesting, perhaps, but let’s bring in report outcomes - the disposition of each incident. The two most common outcomes are “Clear by Citation” and “Clear by Warning”. If we drill down into the first, we can see a huge change between 2021 and 2022: the number of ABCC violations that ended in citations dropped to just 31 last year, compared to 136 the previous year. Warnings, meanwhile, were higher in 2022. What changed? Was this an announced policy?

Good data exploration might provide some answers, but at a minimum it should produce more questions. Some of those might turn out to be pretty good stories.